IN THIS ISSUE

May 2025

When admiring a great voice from the past, you may wonder how this artist could ever have fallen into obscurity. You might just chalk it up to the passage of time. But when you look more closely, you’ll find that there are other reasons why once-renowned greats have faded from view.

Have You Ever Heard Of …

Relatively few opera singers achieve a level of international fame that renders their names immediately recognizable. The assumption that it must be because their singing was somehow lacking would, in many cases, be mistaken. Political events can isolate promising singers from international stages. The failure to land a major recording contract can drastically limit an artist’s audience. Sometimes a singer just slips into oblivion with the passing of decades. There are various reasons why a singer may be unfamiliar, and possibly completely unknown, to the opera lover of today.

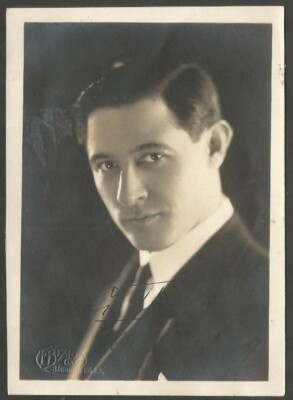

Georges Thill

Born 1897, Paris, France

Died 1984, Draguignan, France

Tragic Endings

Opera history is filled with real-life tragic endings for opera singers. They have made their final exits via heart attack, brain cancer, fatal falls, suicide, and everything else that can befall humanity. Tenor Peter Anders was killed in a car accident at the height of his career, age 46; soprano Arlene Auger died of cancer at 53; and tenor Fritz Wunderlich, age 35, fell down a flight of stairs, dying a few weeks prior to his Met debut.

Died 1958, Rome, Italy

Neri as Mephistopheles

If you like your operatic bassos dark, cavernous, and menacing, Giulio Neri may well be one to add to your Favorites List. Here he is singing “Ecco il mondo” from Boito’s Mefistofele.

Neri debuted in comprimario roles in 1935 and moved to the Rome Opera in 1938 as a leading basso. La Scala welcomed him in 1941, and he began singing outside of Italy after World War II (London, Barcelona, Munich, and Argentina).

Neri’s voice, a basso profondo, was large and commanding, with a powerful on-stage presence. The darkness of his timbre made him ideal for roles of authority, as varied as the Devil, the Grand Inquisitor, Kings, and High Priests. Here he is as Baldassarre, the Superior in the Convent of St. James in Donizetti’s La Favorita, singing “Splendon più belle” and showing off his low C2.

Neri was featured in six complete opera recordings by Cetra Records and was acclaimed for his portrayal of the Grand Inquisitor in Verdi’s Don Carlo. Here he is in the remarkable confrontation scene with King Phillip II of Spain, sung here by Boris Christoff.

At the age of 48, at the height of his career, Giulio Neri died suddenly of a heart attack, and the world of opera lost one of its greatest bassi profondi.

Behind the Iron Curtain

During the Cold War (1947-1991), the term “Iron Curtain” symbolized the efforts of the USSR to isolate itself from the liberal democracies of the “free world.” During that time, Soviet singers, highly prized by the government, were rarely granted exit visas to perform in western countries. While U.S. audiences heard a few outstanding Soviet singers, most were never seen outside of the borders of the USSR, becoming known in the West only through their recordings. Fortunately, they are plentiful.

Irina Arkhipova

Born 1925, Moscow, USSR

Died 2010, Moscow, Russia

Who makes their Met debut at age 72?! That would be the great Soviet mezzo-soprano, Irina Arkhipova, who, after a highly successful 40-year singing career, entered the Russian Hall of Fame. She also had a small planet (#4424) named after her!

Having first studied architecture, Arkhipova entered the Moscow Conservatory late, at age 28, and made her Bolshoi debut three years later (1956). For the next 20 years, she dominated the mezzo repertoire, singing not only roles in Russian operas but also those by Verdi, Wagner, Bizet, Massenet, Mascagni, and Gluck.

Travel visas during the Cold War (1947-1991) were hard to come by, and Arkhipova first appeared in the West during the 1960-61 season as Bizet’s Carmen at the San Carlo Opera in Naples and in Rome. Watch her here in the final scene of Carmen in a live performance at the Bolshoi in 1958, with Mario Del Monaco chewing up the scenery in the old Italian style. (He sings this French opera in Italian, while the rest of the cast sings in Russian.)

In 1963 she made a sensational tour of Japan, and in subsequent years performed at La Scala and in Paris with the Bolshoi. Her first performance in the U.S. took place in San Francisco in 1972 as Amneris in Verdi’s Aida. Here she is in the Judgment Scene of that opera, live from the Bolshoi in 1962, with Ivan Petrov as Ramfis.

Covent Garden got to hear her as Azucena in 1975, and not again until 1988, by which time (at age 63 and after 34 years of singing) her voice was rather “muted,” as one critic wrote.

Nonetheless, at the age of 72, Arkhipova made a belated Metropolitan Opera debut in March 1997 as Filipyevna in Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin.

Arkhipova’s vocal range permitted her to sing the highest mezzo roles to the lowest contralto roles. Her portrayals were authoritative, sharply characterized, and always wonderfully musical. She sang over 40 roles, recorded over 20 operas and several solo albums, selling millions of copies, and was married to Russian tenor Vladislav Pyavko.

Here you can watch the two singing a scene from Moussorgsky’s Khovanshchina, Marfa being one her most famous Russian roles.

Irina Arkhipova died of heart failure at the age of 84.